When Shared Living Isn’t Really Shared Living

Most projects labelled as “co-living” today aren’t truly built for it.

They’re often just conventional rooming houses or apartments with a rebranded leasing strategy, a few smaller units, a shared kitchen, and a new name.

But genuine shared living is not a marketing idea. It’s an architectural, operational, and cultural system designed around how people live together.

The distinction matters because a building that isn’t purpose-built for shared living will always struggle to deliver the experience, stability, and operational efficiency that define the model at its best.

Defining Purpose-Built Shared Living

A Purpose-Built Shared Living (PBSL) project is a building designed, constructed, and operated specifically for long-term communal living.

It differs from standard residential apartments or retrofitted rooming houses in one crucial way: shared living is the organising principle, not an afterthought.

In Australia, only New South Wales has formally recognised co-living as a distinct housing typology under its planning system. However, there is no national framework defining what constitutes a purpose-built shared living project.

To fill that gap, we often draw from international benchmarks, such as London’s Large-Scale Purpose-Built Shared Living (LSPBSL) guidance, which outlines best practice for large-scale shared living developments.

Note:

The Large-Scale Purpose-Built Shared Living (LSPBSL) guidelines referenced here do not form part of any Australian legislation. They originate from the London Plan Guidance (LPG) in the United Kingdom and are used solely as an international reference for defining standards and quality benchmarks.

What Makes a Shared Living Project “Purpose-Built”?

London’s LSPBSL framework identifies four consistent pillars that separate true shared living from standard residential or student housing. These principles are equally relevant to the Australian context:

- Private but compact self-contained rooms: typically, 18-25 m², each with an ensuite bathroom.

- Generous communal spaces: shared kitchens, lounges, work zones, and outdoor areas that encourage daily interaction.

- Integrated management and services: on-site or hybrid operators overseeing cleaning, maintenance, and resident engagement.

- Flexible tenancies: leases designed for 3 to 36 months, bridging the gap between traditional rental and hospitality living.

These elements create a housing format that responds to how people actually live today, smaller households, flexible work, and a preference for service and connection over ownership.

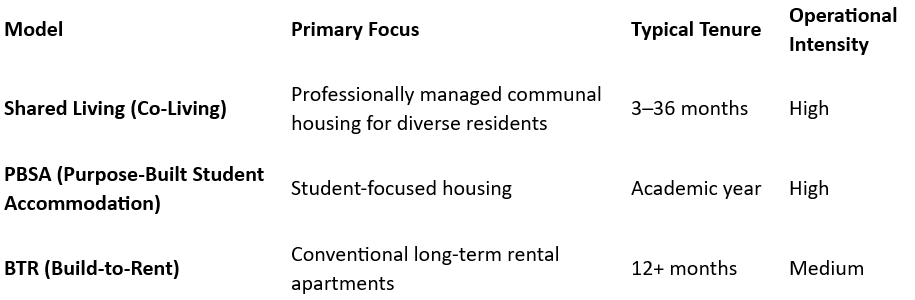

How It Differs from PBSA and BTR

Shared Living or Co-Living sits between PBSA and BTR.

It borrows the community-driven ethos and service model of student housing but adapts it for a broader demographic, including professionals, key workers, and urban newcomers seeking affordability and connection.

Unlike BTR, where residents live privately behind their doors, Shared Living prioritises communal experience, operational service, and social belonging as core components of value creation.

In short, Shared Living is not just about density. It’s about designing for interaction, trust, and efficiency supported by an operator who curates both the physical environment and the resident experience.

Design Principles That Define True Shared Living

Purpose-built shared living projects succeed when design, operations, and community are conceived together.

The strongest models are guided by six design principles:

- Clarity of Typology: Compact private units are intentionally designed for connection to shared spaces.

- Communal Depth: Kitchens, lounges, and outdoor areas typically occupy 20-30% of the gross floor area, distributed for natural flow.

- Operational Integration: Layouts allow efficient servicing, from waste management to staff circulation and maintenance access.

- Safety and Compliance: Designs comply with both residential and short-stay codes, ensuring fire safety, acoustic privacy, and accessibility.

- Social Design: Space encourages informal encounters, shared thresholds, open sightlines, warm materials, and flexible communal zones.

- Adaptability: Furniture, room layouts, and service models are designed for diverse demographics and tenancy lengths.

These principles transform shared living from a leasing format into a living ecosystem.

Operational Standards: The Hidden Architecture

The physical building is only half the story. The other half lies in the operational systems that make it work day-to-day.

Purpose-built shared living requires active management, the kind more common in hospitality than traditional real estate.

That includes:

- Resident onboarding and community orientation

- 24/7 or hybrid building management presence

- Routine cleaning and maintenance cycles

- Digital systems for access, payments, and communication

- Regular community programming to foster connection

Without this structure, shared living collapses into transient renting. With it, the model delivers consistent experience and predictable returns.

Why Purpose-Built Matters

Developers often ask: Can’t we just convert an apartment building into co-living?

You can but you’ll always be fighting the building’s DNA.

A purpose-built shared living asset delivers:

- Higher yield stability through diversified tenancy and shorter voids

- Operational efficiency through shared infrastructure and centralised systems

- Resident wellbeing through human-centred design

- Asset resilience through flexible, future-ready layouts

Purpose-built shared living is not about fitting more people into less space.

It’s about designing smarter spaces where sharing feels natural, dignified, and efficient.

The Path Forward for Australia

Australia’s housing future depends on more than just supply it depends on the right kind of supply.

As affordability pressures rise and household structures diversify, purpose-built shared living offers a scalable, sustainable solution for urban density that remains human.

Livko’s role is to help shape this next chapter working with developers, councils, and investors to define what good shared living looks like in practice.

Because real progress in housing doesn’t come from new labels.

It comes from alignment between how we build, how we operate, and how people actually live